PA

PAWith fewer than 50 council seats left to declare in the Irish local elections, the two biggest government parties are far out in front of their rivals.

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael both have 236 seats. Independent candidates are faring well – they have secured 178 council seats between them.

The main opposition party, Sinn Féin, has won 99 seats so far, well below its own target of 200. The Labour Party has 55 seats and the Social Democrats 35.

Ireland has three EU constituencies which send 14 MEPs to Brussels, and Fine Gael’s Seán Kelly is the first elected, topping the poll in Ireland South.

Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald admitted she was “disappointed” by her party’s council election performance but confirmed she has no plans to step down as party leader.

In total there are 949 council seats to be filled across 31 local authorities.

The Green Party has 23 seats so far, People Before Profit-Solidarity has 13 and Aontú eight.

The current Irish government has been in place since June 2020, when Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and the Green Party voted to enter a coalition together.

Counting is also ongoing for the European parliament elections and a mayoral race in Limerick city.

‘Broad satisfaction’

Fianna Fáil MEP Barry Andrews told BBC News NI’s Good Morning Ulster that the local election results so far show there is “momentum for the government parties”.

“It tells you there is a broad satisfaction with what the government are doing,” he said.

“The fact that the centre held strongly is good news, especially when you look at what’s happening across the EU where there’s been a massive growth in the far right.”

Fine Gael senator Emer Currie added that it was a “good night for the party”.

“We’re offering stability, showing how important the centre and centrist politics is. We are investing in communities and people are seeing that.

“There is enough room in the centre for Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.”

PA

PAMeanwhile, Green Party leader Eamon Ryan told the BBC that the government parties in general have had “a successful campaign”.

However he added that the Green Party will lose “a good number of seats” in the local elections compared to its 2019 performance.

“We expected that because 2019 was really a high water mark for environmental politics right across Europe,” he said.

“But by holding our own in a lot of constituencies, and with a chance of winning two seats possibly in the European elections, we’re still very strong.”

By mid-morning on Monday, the Greens had won 21 council seats.

PA

PASinn Féin disappointment

Sinn Féin expected to have more councillors elected to local authorities than at the previous local election, but so far it has not secured as many as it wanted.

Commentators have suggested the party ran too many candidates which spread its votes too thinly.

There are also internal concerns Sinn Féin failed to make its policy on immigration sufficiently clear to the electorate.

Its leader Ms McDonald has said she will lead a full review into Sinn Féin’s performance.

Sinn Fein TD Padraig MacLochlainn emphasised that the party has “gained seats all around the state but not at the level we would have hoped for”.

“The last local elections in 2019 pretty disastrous for Sinn Fein,” he said.

“This election was always about catch up. We didn’t regain the amount of ground we would have liked.”

New voices cut through

Outside of the main parties, single issues have brought some new politicians to the fore.

In County Donegal, the newly-formed 100% Redress Party fielded six candidates as part of its campaign to secure compensation for victims of the mica scandal.

It fights on behalf of homeowners whose houses are crumbling because they were built with defective concrete blocks containing high levels of the mineral, mica.

So far they have won three council seats and are confident of a fourth.

Immigration was a big issue on the doorsteps during canvassing and in Dublin, two prominent anti-immigration protestors won seats on the city council.

Independent candidate Malachy Steenson, who campaigned against the housing of asylum seekers at a former office block in Dublin’s East Wall area, was elected to represent the North Inner City.

Gavin Pepper, who has protested at several sites which were proposed for migrant accommodation, has been elected in the Ballymun-Finglas ward.

Analysis – Aoife Moore, BBC News NI Dublin reporter

In Ireland, the more things change, the more things stay the same.

The current government party Fine Gael are now the largest party in local government, taking over from their partners in government Fianna Fáil.

As counting continues, the big story from Ireland is the success of independent candidates.

Non-party representatives from all stripes have swept the boards, in both rural and urban areas. In Europe, a similar story has emerged.

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, both centrist parties, are likely to be the first announced MEPs to return to Brussels.

Sinn Féin, who were at one point tipped to shake up the Irish political scene, have failed in their bid to take over local councils but may return to Europe with one MEP.

The party, who were once uncatchable in political polling, have plummeted as the party has struggled to confirm their stance on immigration and housing for asylum seekers.

Their leader, Mary Lou McDonald, said “lessons will be learned” from this experience.

This is her second disappointing local and European election since taking over from Gerry Adams in 2018.

PA

PAWhat is proportional representation/STV?

Reuters

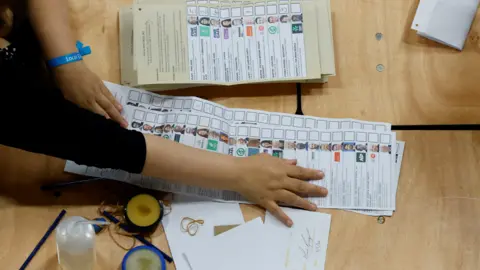

ReutersThe Republic of Ireland uses a voting system known as proportional representation (PR) in all its elections.

Local councillors, TDs (Members of the Irish parliament); Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) and even the president of Ireland are all elected via PR.

Under the PR system, every voter has a single transferable vote (STV).

That means in each constituency, people can vote for as many or as few candidates as they want on the ballot paper, indicating their choices in numerical order.

The PR-STV system means that if a voter’s preferred candidate is eliminated because they got too few first preference votes, those ballot papers can be redistributed to the remaining candidates, based on voters’ second preferences, and so on.

Additionally, if a candidate receives more votes than they need to reach the election quota, their surplus votes can be redistributed, according to the voters’ preferences.

The benefits of the PR election system in contrast to a simple “first past the post” election is that PR tends to offer smaller parties and independents a better chance of winning seats against larger, more established parties.

It also gives voters more of a say over who represents them as they can indicate alternative preferences if their first choice candidate has little hope of winning.

But critics of the PR system argue it can result in weak coalitions coming to power, rather than a government with a strong majority which could rule decisively.

They also argue that PR permits parties to stay in power by forming new coalitions, even when their popularity has declined.