Several of our members have asked about preferred stock. Does it fit in an income factory? If so, where? It’s a good question.

Preferred stock has certain qualities of both equity and debt. How should income investors like us, who focus on maximizing income growth through reinvesting and compounding high yields, regard preferred stock? It obviously appears to have some characteristics that make it a candidate worth considering. The question then becomes, how does it compare with other alternatives, like senior loans and high yield bonds, as well as high-yielding stocks, like utilities, real estate, energy-based MLPs, etc.

Here are some points worth considering:

In considering “fixed income” investments, we need to determine what we are actually “betting on” when we make the investment:

- Corporate loans and high-yield bonds are generally made to non-investment grade corporations, where the primary risk is risk of default (i.e. pure credit risk). There’s very little interest rate risk since loans are “floating rate” with rates re-adjusted every month or quarter, and high-yield bonds are relatively short term (five years or so), so a major portion of your portfolio is being re-priced every year at current “updated” interest rates. Traditional bonds (longer term and lower yields) carry negligible credit risk, but considerable interest rate risk, because if rates move higher, you can be stuck with a substandard return for years, or face a capital loss if you need/want to sell before maturity.

- Credit risk is relatively straightforward to model and manage, especially in the loan market where virtually all loans are secured by collateral, which results in recoveries on defaulted loans generally in the 60%-70% range. Even unsecured bonds usually recover 40%-50%. This means a headline “default rate” of, say, 5% (a recession level default rate) would generally result in losses of only 2%-3%, eating into an investor’s yield but not even touching principal.

- Our “bet” in a well-diversified credit investment is that the hundreds of borrowing companies represented in the funds we own will stay alive and pay their debts. For taking this risk we are paid a yield, as we will see below, currently in the 10%-11% range for corporate senior loans and high-yield bonds. As mentioned above, defaults in the 5% range (much higher than we’ve experienced in recent years) would knock that yield down to the 7%-8% range in a given year, but wouldn’t invade principal.

- By contrast, an equity investor is betting that a company (or many companies, if they invest via a fund) will not only stay alive and pay their debts (the bare minimum) but will also thrive and grow so that their earnings and dividends increase. If all the companies do is survive but don’t thrive and grow, then their creditors will be happy, but their stockholders will likely be very disappointed.

- It should be obvious that an equity investor is taking the same credit risk as a loan, bond or fixed income investor that the company will fail to survive and pay its debts. But besides that, it is taking the additional risk that the company will stagnate and ONLY survive, while failing to grow and make its stock worth more.

- This is why it is important that if you invest in stocks, that your returns should be more than those of a credit investor who is only taking the “existential” risk of defaulting and going bust, but is not taking the additional “entrepreneurial” risk of failing to grow its business and earnings.

These issues become important when we assess the attractiveness of preferred stock, which resides somewhere midway between debt (i.e. credit investments) and equity.

- Like debt, most preferred stock (unless it’s “convertible preferred,” which is essentially a deeply subordinated bond with an equity option attached to it) is fixed in that it has no upside that grows along with the issuer’s performance, the way equity does.

- But unlike most loans and bonds, most preferred stock has no expiration (i.e. maturity) date, so the risk that its dividend yield may become out of sync (i.e. too low) compared to prevailing interest rate levels is much greater than a fixed term bond where the investor knows that they will at least get their principal back at par on a known future date. So if a preferred stock’s price drops because interest rates rise, an investor may have no choice but to hold it indefinitely and collect a sub-standard yield, or sell out at a loss. Issuers sometimes “call” preferred stocks in and pay them off, but they have no incentive to do that if the rate on the preferred is low, by current market standards; only if the rate is higher. So if an investor is smart or lucky enough to buy a preferred at an unusually high rate, that’s the one the issuer will want to pay off as soon as possible.

- In addition, when companies do default, preferred stock is at the bottom of the liability stack, and gets paid nothing unless and until the senior secured loans and the unsecured bonds above them are repaid in full.

So preferred stock has the worst of all worlds in some ways, in that it has none of the upside that regular equity does, but it also has none of the protections in terms of collateral or priority in the liability pecking order that loans and bonds have. This is why most preferred stock is issued by fairly well-established investment grade companies, where the risk of default is less than that of the typical non-investment grade companies that issue senior loans and high yield bonds.

Bottom Line:

- In terms of protection, if the issuer’s credit should go south, and it defaults or goes bust, the preferred stock investor is no better off than a stockholder.

- However, if the company does well and grows, the preferred stock investor does not participate in the upside.

- The only advantage the preferred stockholder gets is a higher cash yield than the stock dividend that normal equity holders get.

- On the other hand, they’re generally less well compensated from a yield standpoint than the debt above them (loans and bonds), and of course they have none of the protections that those loan and bondholders have in the event the company defaults.

Now let’s look at the numbers, to see if the results bear out the theory.

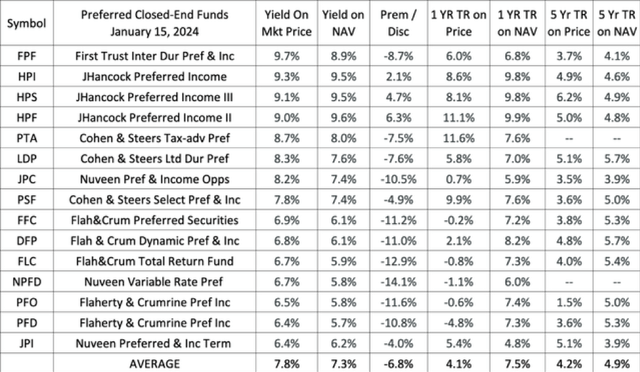

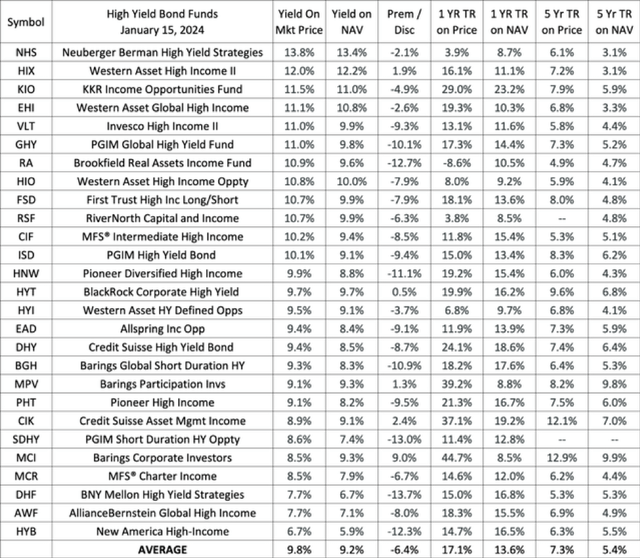

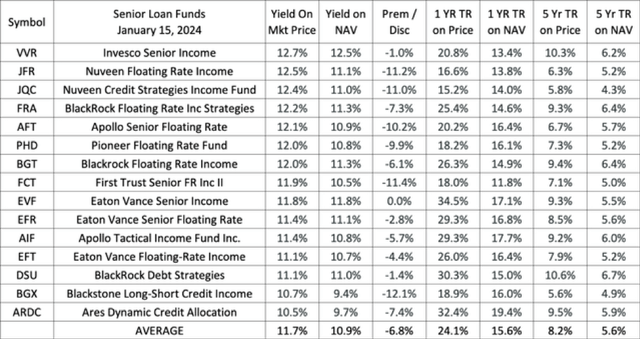

Here are the lists of (1) preferred stock funds, (2) high-yield bond funds, and (3) senior loan funds covered by CEF Connect. I sorted by those three categories, and then parsed the lists to remove funds that were mislabeled or weren’t “real” members of the category. For example, there were funds holding collateralized loan obligations ((CLOs)) listed as loan funds, and some other loan and bond funds that held other more exotic investments too, which I removed to keep the lists fairly “generic.” I ranked them by distribution yield, just as a starting point for comparisons.

CEFConnect

CEFConnect

CEFConnect

Here’s a summary of the results:

SB

As you can see, the preferred stock funds, while they have provided reasonable returns, have not come close to matching the recent returns of our credit investments, either from a distribution yield standpoint or in terms of total return. This is why I have emphasized loan and HY bond funds in my personal portfolio, as well as in my “core” model portfolio, both of which aim to focus primarily on the “yield” component of their total return, with capital gains, if achieved, being icing on the cake.

If preferred stock funds have a place in an Income Factory portfolio, it may be in taxable portfolios, where the qualified income they generate (because they pay dividends, not interest) will likely be taxed at lower rates. Then we have to ask ourselves if we want to settle for the lower total returns (because preferred stockholders sacrifice the chance to earn the capital gains that “real” equity funds provide us) in order to get slightly higher distribution yields.

I look forward to your comments and questions, and thank those readers who raised the question and caused me to focus more intensively on this interesting topic.